Internal Guidelines for Adaptive Management for Cold Stun Closures

Dec. 14, 2016

I. Issue

Since 2011, the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries (NCDMF) has followed a set of guidelines to determine if closing the spotted seatrout commercial and recreational fisheries after severe winter cold stun events are warranted (NCDMF 2012). The decision to close the fishery is left to the discretion of the director after significant cold stun events have been reported in at least four North Carolina counties. There were reported cold stun events during the winter of 2014-2015, but it was determined a closure was not warranted. Afterwards, members of the public expressed concern with the current guidelines, citing a perceived subjectivity by the NCDMF staff and its director when classifying a cold stun as “significant.

II. Origination

After the winter of 2014-2015, members of the public and the North Carolina Marine Fisheries Commission (MFC) expressed concern over the current cold stun closure guidelines and voiced a desire to change the current strategy. Subsequently, the director instructed NCDMF staff to investigate alternative options for spotted seatrout cold stun closures, including a more quantifiable metric to trigger action.

III. BACKGROUND

Spotted seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus) and other finfish that over-winter in estuarine environments in North Carolina are susceptible to periodic cold stun events. These events are caused when water temperatures fall below a fish’s metabolic thermal minimum, inducing loss of equilibrium and immobilization. If periods of sub optimal water temperatures persist and fish are unable to move to warmer waters, mortalities can occur. In North Carolina, coldstun events can be triggered by snow and ice melt following a winter storm or by prolonged below average air temperatures from periodic arctic cold fronts. The former is more characteristic of early winter cold stuns where water temperatures in creeks and bays can change rapidly from cold water runoff, and the latter is more typical later in the winter when water temperatures gradually fall below the optimal temperatures for the fish and induce cold stun from long-term exposure. Cold stun events can be localized to single river systems, and even individual tributaries; or they can be widespread across multiple estuaries or even statewide if conditions are right. Mortalities from cold stuns have been identified as a factor contributing to variable natural mortality in spotted seatrout (Ellis 2014; NCDMF 2009, 2015). It has been suggested that declines in spotted seatrout abundance may be due, in some part, to mass mortalities from severe cold stuns. Mass mortality events observed in North Carolina from cold stuns have been an historical occurrence and have occurred as recently as the winters of 2000, 2002, 2004, 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2015.

As a response to the results of the 2009 Spotted Seatrout Stock Assessment and public concern over the detrimental effects of frequent cold stuns on the spotted seatrout stock, the MFC, upon its approval of the Spotted Seatrout Fishery Management Plan (FMP), decided not to develop a protocol for cold stun closures. Rather, the MFC instructed the director to “Remain status quo with the assumption that the Director will intervene in the event of a catastrophic event and do what is necessary in terms of temporary closures by water body” (NCDMF 2012). Subsequently, the director instructed NCDMF staff to develop an adaptive management approach for determining when a closure was necessary and the duration of that closure. Lead staff and the Spotted Seatrout Plan Development Team (PDT) developed the current guidelines with input from the MFC (February 2012). Currently, for the director to issue a proclamation to close the spotted seatrout fishery, verifiable cold stunned fish must occur in at least four counties. If this condition is met, at the director’s discretion the fishery is closed until June 15 of the following spring. Keeping the fishery closed until late spring affords mature fish that survived the winter the opportunity to spawn at least once before the fishery reopens.

Since the first FMP for spotted seatrout (NCDMF 2012) and the development of the cold stun closure guidelines, the director has issued proclamations closing the commercial and recreational spotted seatrout fisheries twice for meeting the conditions triggering action outlined in the guidelines (Proclamation FF-7-2011; FF-30-2011; FF-9-2014). During the winters of 2011 (December 2010 — January 2011) and 2014 (February 2014), cold stunned fish were observed in many coastal counties and air and water temperatures remained very low for days to weeks. During these events, members of the public expressed desire to have the fishery closed and NCDMF was confident that the cold stun was wide-spread and severe enough to warrant a closure under the cold stun closure guidelines.

During the winter of 2015 (February 2015), cold stunned fish were observed in some of the southern Neuse River tributaries, Bay River, and southern Hyde County bays. Cold stunned fish were localized to small tributaries mostly on the southern portion of the river systems. Most reports of stunned fish from the public were unverified or inconsistent with what was observed by NCDMF staff in the field. For this event, NCDMF staff determined that the four-county threshold was not met and the director did not choose to close the fishery. This decision was unpopular with some members of the public. Their opinion was that the low landings from 2015 were a direct result of the cold stun that occurred earlier in the year and a closure may have saved more adults for the spring spawn. The public expressed frustration with the perceived subjectivity of a significant cold stun event and the decision to not close the fishery under the current closure guidelines. The director then asked lead staff to develop an adaptive management approach that was more objective and quantifiable.

IV.Discussion

Until recently, empirical estimates of sublethal thermal minimums and lethal acclimated chronic exposure times were not available for spotted seatrout in their northern range. Anweiler et al. (2014) exposed hatchery reared age-0 fish to rapid declines in water temperature (1 °C [1.8 °F]/day) to determine the absolute lethal minimum and also chronic exposure to static and fluctuating sub lethal temperatures (5.25°C [41.5°F] and 4.25°C [39.7° F]) to evaluate prolonged lethal exposure. Fish lost equilibrium at an average critical thermal temperature of 3.57°C ± 0.24°C (38.4°F ± 0.43 °F) and suffered mortality at an average temperature of 3.08 °C ± 0.31°C (37.5 °F ± 0.56 °F). Survival was significantly different between the two static temperature treatments with the highest mortality occurring at 4.25°C (39.7°F). However, fluctuations around the temperatures did not have a significant effect on survival compared to the static treatments. Ellis et al. (2016; in review) took this experiment a step further and introduced the covariate of salinity as well as performing the experiments with larger age-0 and age-1 fish harvested from North Carolina estuaries. They observed that fish exposed to rapid changes in water temperature (1 °C [1.8 °F]/hour) lost equilibrium at temperatures ≤ 3.5°C (38.3°F), similar to the Anweiler et al. (2014) study. Mortality induced from long-term exposure was evaluated at three discrete temperatures (3°C [37.4°F], 5°C [41°F], and 7°C [44.6 °F]) and two salinities (10 and 30 PSU) for a 10-day period. Salinity did not have a significant effect on survival within each of the temperatures but survival across all the temperature treatments was different. All fish exposed to 3 °C (37.4 °F) water did not survive after two days with an estimated 50% probability of survival after one day. At 5 °C (41 °F), most fish survived up to five days before mortalities started to occur and by day eight estimated survival probabilities fell below 50%. Mortalities were low for fish exposed to 7 °C (44.6 °F) with survival probabilities of approximately 90% at the end of the 10-day period.

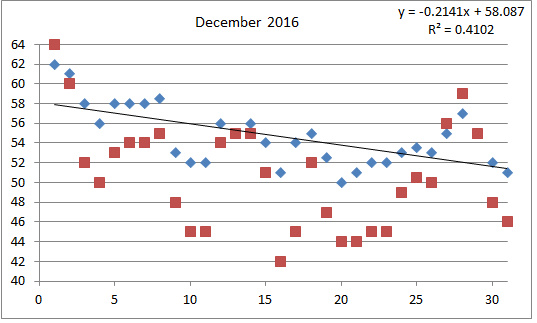

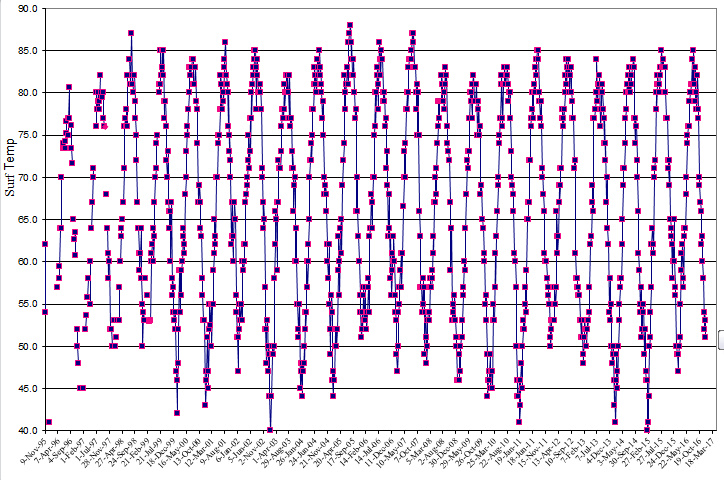

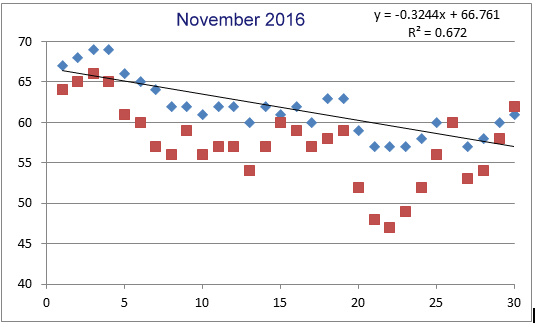

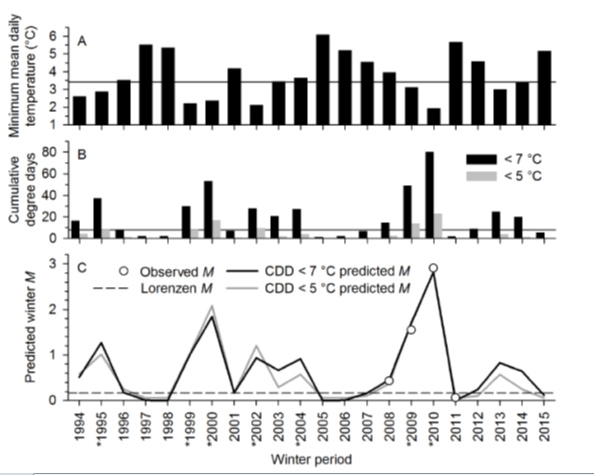

Ellis et al. (2016; in review) then developed a temperature-based model for predicting the natural mortality (M) of spotted seatrout in the winter based off of the laboratory results and observed estimates of natural mortality from tagging data. Natural mortality based on the annual cumulative cold degree days of <7 °C and <5 °C was modeled for the winters of 1994 – 2015 using water temperature data collected from the National Estuarine Research Reserve at Zeke’s Island, North Carolina. The results were compared to observed estimates of M from previous tagging work (Ellis 2014) for the four years it was available (Figure 1). Cumulative degree days at <7 °C and <5 °C for the years modeled varied widely with some years never reaching the temperature thresholds, while others met or exceeded the eight-day exposure limit for 50% survival at 5 °C by almost twofold. In years where confirmed cold stun events occurred, the model predicted high M and CDD exceeded the eight-day threshold. Modeled estimates of M highly associated with observed estimates inferred from tagging data for both the <7 °C (P=0.003) and <5 °C (P=0.004) metrics. Overall, low temperature metrics (CTM and exposure) inferred for spotted seatrout from laboratory experiments are consistent with observed patterns of winter severity and mortality and may be useful for evaluating the impact of future cold stun events to the spotted seatrout stock.

Figure 1. Taken from Ellis et al. (2016; in review). Minimum winter (November – February) mean daily temperatures (A) and cumulative cold degree days (CDD) of temperatures < 7 °C (black) and < 5 °C (grey) occurring during the winter period (B). Horizontal line indicates the laboratory estimates of critical thermal minimum (3.57 °C ± 0.24°C) and 50% mortality at 5 °C over eight days for panels A and B, respectively. Rate of natural mortality (M) of spotted seatrout estimated for each winter using the predictive model developed with both temperature metrics (black and grey lines), observed natural mortality inferred from tagging data (open circles), and the Lorenzen weight-based estimate of winter natural mortality used during the previous spotted seatrout stock assessment (NCDMF 2012). Asterisks next to winter periods denotes years where cold stuns were have known to occur.

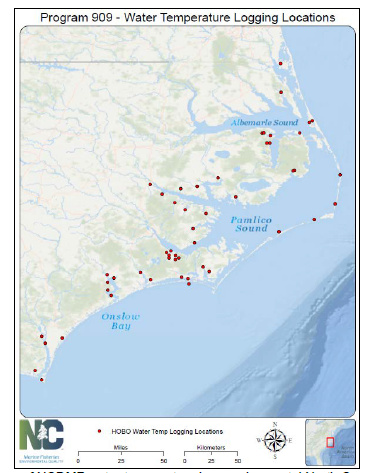

In 2015, the NCDMF started a comprehensive, statewide water quality monitoring program (program 909) and deployed a statewide array of continuous water temperature loggers and data sondes. A total of 80 loggers at 55 stations measure water temperature every 15 minutes. Station locations are distributed throughout coastal North Carolina with specific locations that staff felt were representative of the riverine and estuarine systems they were in and locations of historical occurrences of cold stuns (Figure 2). At depths greater than 2 meters, two loggers were placed to monitor temperatures at the surface and bottom to help managers identify water column stratification and turnover events. In addition to the 80 temperature loggers, the NCDMF also deploys and maintains around 25 water quality data sondes that also collect water temperature data. These sondes are located mostly in Albemarle and Pamlico sounds and are used for monitoring water quality for alosine habitat and artificial reef conditions.

Figure 2. Locations of NCDMF water temperature loggers in coastal North Carolina.

Given what is now known about spotted seatrout temperature tolerances and available water quality data from the NCDMF temperature loggers and data sondes, more quantitative information can be used in determining the necessity of a fishery closure. Better understanding of spotted seatrout physiology can allow for quantitative temperature triggers that incorporate estimated probabilities of survival to provide the director with a measurable metric to inform his decision on a spotted seatrout fishery closure. However, due to unequal distribution of spotted seatrout throughout its overwintering habitat, a closure should not be based on temperature alone. The reported presence of cold stunned fish should also be considered when making this decision.

The spatial extent of cold stun events should be considered when evaluating the efficacy of a fishery closure. Historically, cold stun events have varied in their spatial coverage and have ranged from a few isolated creeks in one river system to multiple riverine and estuarine systems. Wind and tidal influences on water temperature can cause areas on the windward side of a river or estuary to turnover and trap fish in tidal creeks and bays causing rapid drops in water temperatures and inducing a cold stun. An example of this phenomenon occurred during the winter of 2014-2015 in the Neuse River. Strong northerly winds coupled with below average air and water temperatures acted to “push” cold surface waters south into the creeks around Havelock. This cold water displaced the warmer water in the creeks and caused a water column turnover event trapping spotted seatrout and many other fish species in the headwaters of the creeks and causing a localized cold stun event. However, on the leeward side of the river, water temperatures did not change drastically and no cold stunned fish were observed or reported. Cold stun events can also occur over large areas of the state when light winds and clear night skies, along with prolonged below average air temperatures, act to cool the water down. This gradual decrease eventually drops bottom water temperatures to a point that can be lethal to spotted seatrout. These cold stun events can affect the entire coast causing catastrophic losses in all major riverine and estuarine habitats.

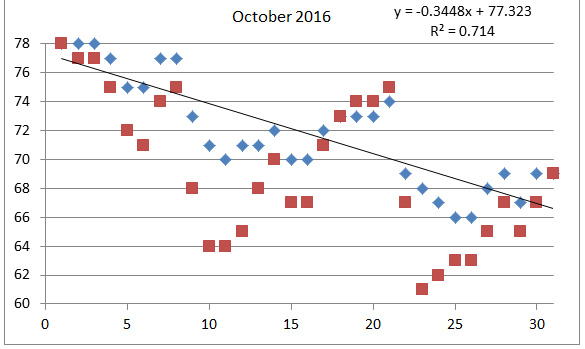

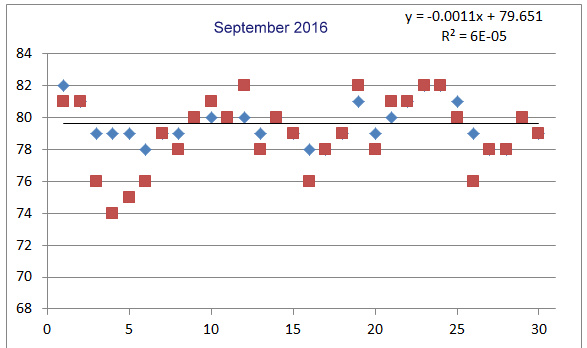

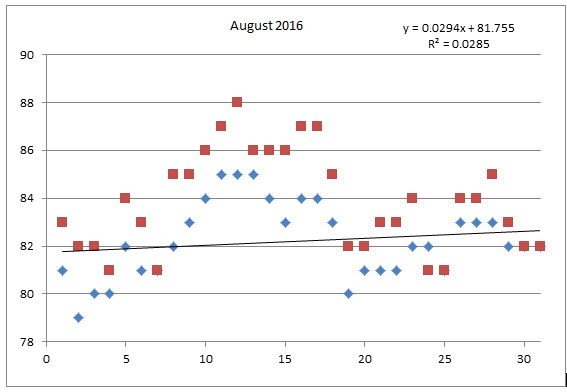

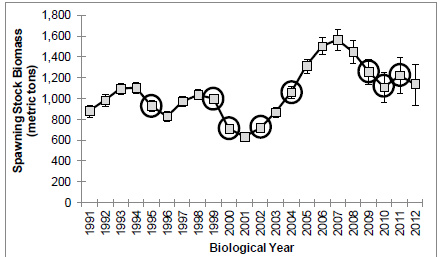

The spotted seatrout fishery has only been closed twice in the history of the state due to population concerns from cold stun events, both occurring in the last decade in 2011 and 2014. However, cold stun events have occurred in North Carolina for centuries with written reports since colonial times (Lawson 1709). The life history of spotted seatrout is well suited for high and variable rates of annual mortality and often population level impacts from cold stun events are only evident for the year directly following a cold stun event (Figure 3). However, years with back to back cold stun events can prolong a rebound of the population. The original intent behind closing the spotted seatrout fishery was to protect mature fish from harvest after a cold stun to allow time for the fish to spawn and hopefully encourage the rebound of the population. Yet, rebounds in the population have been observed as early as the following year after cold stun events where no closure was instituted and commercial and recreational regulations were less strict than today. Additionally, it is difficult to determine if a closure significantly affects recruitment of fish the following year due to the current spotted seatrout assessment terminal year of 2012 (only one closure in the time series) and the difficulty of incorporating water temperature effects on natural mortality into the model. Not having an option to close the spotted seatrout fishery after a significant cold stun event goes against the recommendations of the MFC and comments from members of the public. Because this option would be against the recommendation of the MFC, it is not considered a viable option for the NCDMF adaptive management approach to cold stun closures and is presented here for informational purposes only.

Figure 3. Predicted spawning stock biomass (SSB) for spotted seatrout annually from 1991-2012. Circles indicates years when cold stun events occurred (NCDMF 2015).

Maintaining status quo with the current cold stun closure guidelines would be against the desires of the public. The inherent subjectivity of the current closure guidelines creates a loss of trust between the public and fisheries managers of the state and does not allow for objective, quantifiable metrics to inform the decision of a fishery closure. Also, current closure guidelines do not allow for regional closures, only statewide closures. This adversely affects fisherman in areas of the state where no cold stun has occurred and the impact to the local spotted seatrout population is minimal. However, the recommendation from the MFC for management of cold stuns gives the director the authority to close the fishery in the state, by region, if they so choose after a significant cold stun event. The director has never closed the fishery by region because cold stun closures have been issued under the current guidelines which require at least four counties to experience significant cold stuns. The areas of the state that are most frequently impacted by frequent, severe cold stuns are located in a few, large coastal counties. Closures under the four-county guidelines preclude regional closures because to meet the four-county threshold, so much of the state’s waters would have to be impacted and a statewide closure is usually the most prudent option. A modification of these guidelines to remove the four-county threshold will provide the director the opportunity to close the fishery by regions after significant cold stuns are reported. These regions can range in size from specific water bodies to statewide at the director’s discretion.

Given new information available about spotted seatrout temperature tolerances, mortality probabilities to sub optimal temperature exposure, and available continuous water temperature monitoring, management options can now incorporate quantitative thresholds to trigger closures. There is also the option to have these closures vary by spatial extent from statewide to individual river systems. Based on survival probabilities generated by Ellis et al. (2016; in review), average water temperature and exposure triggers of 5°C (41° F) at eight consecutive days and 3 °C (37.4 °F) during a consecutive 24-hour period should be considered. At these water temperature and time combinations, it is reasonable to assume that about half the fish exposed to these temperatures will succumb to mortality. When temperature triggers are met and cold stunned fish are observed and verified by NCDMF staff within a management unit, the fishery could be closed in that unit until the following spring. A statewide closure will protect all spotted seatrout in North Carolina ensuring that areas that do not have water temperature monitoring coverage but may still experience cold stun conditions are protected. However, this strategy will cause fishing opportunities to be lost in areas that may not be affected by cold stun conditions.

A regional approach incorporating the 5 P°PC (41 °F) at eight consecutive days and 3 °C (37.4 °F) during a consecutive 24-hour period within a management unit could preserve fishing opportunities in unaffected areas and protect surviving fish in areas where cold stun events occurred. Tagging and genetics data suggest that spotted seatrout exhibit high site fidelity to their natal estuary with periods of greater movement during the spawning season (Ellis 2014; O’Donnel et al. 2014; Ward et al. 2007; Bradley and Chapman 2003). This, coupled with the limited movement of spotted seatrout during the winter months (Ellis 2014), support that the effects of a cold stun may vary regionally. By splitting the state into cold stun management zones, largely based on major riverine and estuarine systems, managers will have the ability to close areas where cold stun events occur while preserving fishing opportunities in others. However, fisherman from a closed area may move to an open area shifting and concentrating the effort and fishing mortality from one area to another.

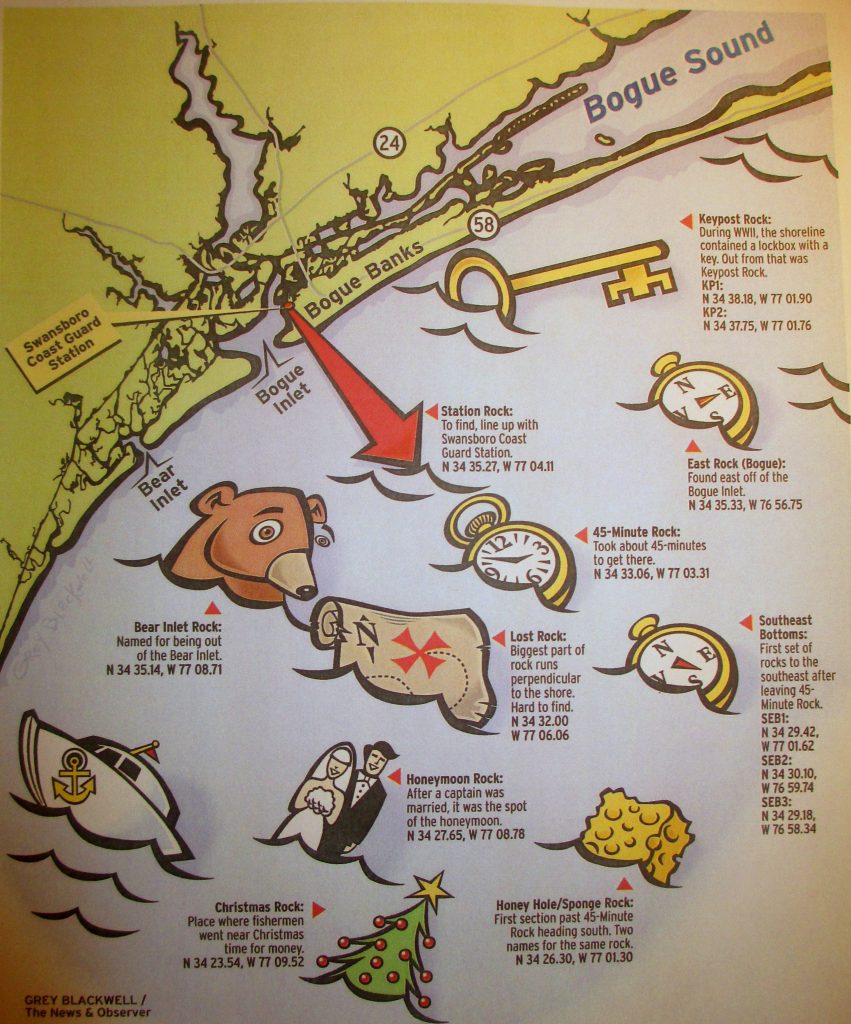

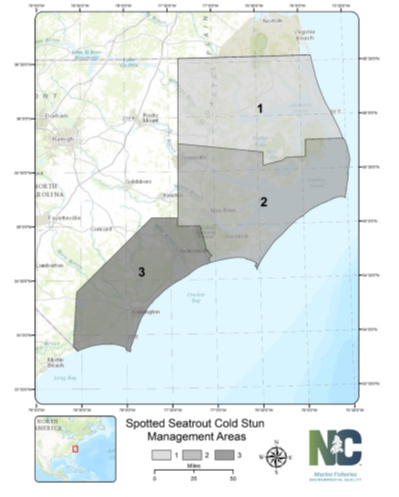

Cold stun closure regions should be broad enough spatially to encompass major estuarine and riverine systems where spotted seatrout overwinter and allow for adequate protection from fishing pressure after a closure is enacted until the following spring spawn has begun. The closure should extend through the peak of the spawning period of spotted seatrout and the closed region should be broad enough to protect fish from fishing pressure in the cold stun-affected area, as well as in areas where the species aggregates to spawn. In North Carolina, spotted seatrout spawn near seagrass beds, sandy banks and oyster reefs in and around creek and river mouths from April until October, with a peak spawn occurring around May and June (Burns 1996; Luczkovich et al. 1999). If possible, currently delineated management areas that meet the previously stated characteristics should be considered for cold stun closure regions. Continuity of management units among different management programs would aide Marine Patrol in enforcement of closures due to familiarity of boundaries and not burden fisherman with learning additional boundaries. The estuarine gill net management areas used by NCDMF to manage the estuarine gill net fishery for sea turtle interactions meet all of these considerations. The management units were delineated based on the similarity of fisheries occurring within them, similar water quality and habitat conditions, and the ability of NCDMF Marine Patrol to monitor fishing effort (NCDMF 2013; NCDMF 2014b). The spatial extent of these units are broad enough to cover the primary riverine systems of the state that are typically impacted by cold stuns and allow enough spatial coverage to protect fish spawning in these areas before the fishery is opened after a closure. However, for the estuarine gill net management units, the central portion of the state was divided into four regions based on historical sea turtle abundance in western Pamlico and Core sounds. For the purposes of cold stun closures, NCDMF staff decided to combine units B, C, D1, and D2 into one management area (Figure 4). The new cold stun management areas combine the major riverine and estuarine regions of the state into three discrete spotted seatrout cold stun management areas:

- Area 1 includes the Albemarle Sound and all its tributaries including Crotoan, Roanoke, and Currituck sounds;

- Area 2 encompasses all of Pamlico Sound, Tar-Pamlico and Neuse rivers and their tributaries, and all coastal waters in Carteret County from the Highway 58 bridge east; and

- Area 3 includes all of the southern coast south of Highway 58.

These broad management areas allow for affected fish, if they survive, to recover and spawn the following spring with the reasonable expectation that they will not be persecuted by a fishery within that area due to their limited movement during this time.

Figure 4. Map of the Spotted Seatrout Cold Stun Management Areas.

Water temperature loggers require physical download to retrieve water temperature data which can delay the response time of NCDMF staff when investigating cold stun events. To speed up the time it takes to compile the water temperature information needed to make a decision on a fishery closure, NCDMF staff will monitor air temperature, weather forecast, and winter precipitation events during the winter months and download data from loggers when conditions are favorable for cold stuns. The cold stun of 2010-2011 occurred after a winter storm that covered much of eastern North Carolina in snow and ice and caused ice to accumulate on many creeks and shallow bays. The subsequent runoff of melted snow and ice entered the creeks and estuaries causing drops in water temperatures, which led to the severe cold stun event that occurred that winter. In contrast, the cold stun in February of 2014 occurred during a long period of below-normal air temperatures which gradually caused water temperatures to drop across the state. To ensure a timely response to future cold stuns, NCDMF staff will begin to download water temperature loggers and monitor coastal waters for affected fish when weather conditions when similar weather conditions are expected.

The director has managed spotted seatrout fishery closures under the current closure guidelines with the interpretation that a significant cold stun event has to occur in at least four counties statewide before a closure is warranted. Ambiguity among the public and NCDMF staff over what constitutes a significant cold stun event in North Carolina has caused public concern. To remove some of the inherent subjectivity in deciding if a cold stun is significant, a quantifiable measure of the number of stunned or dead fish is needed. The North Carolina Division of Water Resources (NCDWR) monitors and reports on fish kill activity across the state and has developed protocols for classifying fish kills. NCDWR classifies a fish kill as at least 25 fish affected and verified by trained staff (NCDWR 2015). Cold stunned spotted seatrout in natural settings can vary in their observed condition from visably lethargic and slow to respond to external stimuli, to visable leisons and necrotic skin, to dead and rotting. Cold stuns ususally affect all spotted seatrout within an area and it can be assumed that if less than 25 cold stunned fish are observed and verified, then the number of spotted seatrout in that area is low and the impacts from a cold stun would be minimal.

V. Guidance

Manage cold stun closures for spotted seatrout regionally (Figure 4) through an adaptive approach, taking into consideration:

- The size and scope of a kill and temperature exposure;

- The rate at which water temperature can change from cold-water runoff or prolonged below-average air temperatures; and/or

- The evaluation of water temperatures and exposure triggers of 5°C [41°F] at eight consecutive days and 3°C [37.4 °F] during a consecutive 24-hour period.

VI. LITERATURE CITED

Anweiler, K. V., S. A. Arnott, and M. R. Denson. 2014. Low-temperature tolerance of juvenile spotted seatrout in South Carolina. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 143:999-1010

Bradley, A. W and R. W. Chapman. 2003 “Population structure of spotted seatrout, Cynscion nebulosus, along the atlantic coast of the U. S.” Biology of spotted seatrout, Edited by S. A. Bortone. CRC PressBoca Raton, Florida. 31-40 p.

Burns, B. 1996. Life history aspects of marine recreational fishes in North Carolina. North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries, Project F-43, Morehead City, North Carolina. 25 p.

Ellis, T. A. 2014. Mortality and movement of spotted seatrout at its Northern latitudinal limits. Dissertation North Carolina State University. 258 p.

Ellis, T. A., J. A. Buckel, J. E. Hightower, and S. J. Poland. 2016. In review. Relating cold tolerance to winterkill for spotted seatrout at it northern latitudinal limits. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

Lawson, J. 1709. A new voyage to Carolina. London, England. 270 p.

Luczkovich, J. J. R. C. Pullinger, S. E. Johnson and M. W. Sprague. 1999. Identifying the critical spawning habitats of sciaenids using passive acoustics. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 137: 576–605.

North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. 2009. Stock Status of Spotted Seatrout, Cynoscion nebulosus, in North Carolina, 1991-2008. NCDMF, Morehead City, North Carolina. 90 p.

North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. 2012. North Carolina Spotted Seatrout Fishery Management Plan. NCDMF, Morehead City, North Carolina. 344 p.

North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. 2013. Application for an individual incidental take permit under the endangered species act of 1973. NCDMF, Morehead City, North Carolina 154 p.

North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. 2014. Application for an individual incidental take permit under the endangered species act of 1973. NCDMF, Morehead City, North Carolina 165 p.

North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. 2015. Stock Assessment of Spotted Seatrout, Cynoscion nebulosus, in Virginia and North Carolina Waters. NCDMF, Morehead City, North Carolina. 142 p.

North Carolina Division of Water Resources. 2015. North Carolina Division of Water Resources Annual Report of Fish Kill Events 2015. NCDWR, Raleigh, North Carolina. 16 p.

O’Donnel, T. P., M. R. Denson, and T. L. Darden. 2014. Genetic population structure of spotted seatrout Cynoscion nebulosus along the Southeastern U.S.A. Journal of Fish Biology. 85:374-393.

Ward, R., K. Bowers, R. Hensley, B. Mobley, and E. Belouski. 2007. Genetic variability in spotted seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus), determined with microsatellite DNA markers. Fisheries Bulletin. 105:197-206.

This document was prepared by Steve Poland (Steve.Poland@ncdenr.gov) with input from the NCDMF Spotted Seatrout Plan Development Team and Management Review Team.